GUEST BLOG: THE PERFECT STORM OF 1982

Guest writer Steven gives us his thoughts on a period which so nearly proved fatal for the club...

The early 1980s are a source of fascination to me, in a kind of car-crash manner. You know you shouldn't look, and it's going to be horrible, but somehow you just can't pull your eyes away. I'm old enough to remember what happened, yet young enough that it all washed over me. What had actually happened to my beloved club, and what was all the talk about it closing down? Just how did the Bhattis get their hands on things? So, in order to get it out of my system, I thought I'd investigate for myself what caused one of England's top sides to go within three minutes of closure back in the days where the penalties for relegation were not so severe. And I've come to the conclusion that what happened was a "Perfect Storm", a whole load of circumstances coming together in exactly the way to cause maximum damage, at precisely the wrong time.

The team

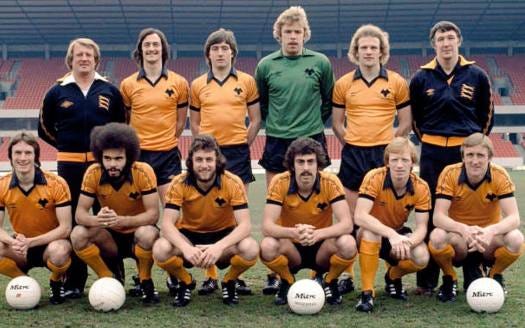

In the summer of 1980, we had a pretty good side. Good enough to win the League Cup back in the days when everyone wanted to. Good enough to finish sixth in the old First Division. We'd got a decent manager, and things were rosy all round as we looked forward to the UEFA Cup, and a tie against PSV. In our more positive moments, we thought that we might just beat the side of 1972, and actually win the thing. In the end, we fell horribly short. Out in the first round of the UEFA Cup, out quickly in the League Cup, struggles against relegation in the First Division, finally ending up 18th. Only the FA Cup brought some measure of success, as we made it through to the semi-final and really should have won the replay handsomely. What went wrong on the pitch? In order to answer that question, we'll take a look at the 1980 League Cup Final team, as it was pretty much our first choice line-up that season. It's embedded in my brain:

1. Bradshaw

2. Palmer

3. Parkin

4. Daniel

5. Hughes

6. Berry

7. Hibbitt

8. Carr

9. Gray

10. Richards

11. Eves

Looks a pretty decent side on the surface, doesn't it? If you look a little deeper, a somewhat darker picture emerges. At the end of 1980, they were the following ages, with their dates of joining Wolves. Bradshaw (24, 1977), Palmer (26, 1971), Parkin (32, 1968), Daniel (25, 1978), Hughes (33, 1979), Berry (23, 1976), Hibbitt (29, 1968), Carr (30, 1975), Gray (25, 1979), Richards (30, 1969), Eves (24, 1975) .

In those days, footballers' careers did not last as long as today, so of that lot, pretty much half the team (Parkin, Hughes, Hibbitt, Carr and Richards) would need replacing soon. There were no really good young reserves, bar Wayne Clarke and John Humphrey, and of the rest John McAlle was also on the wrong side of 30 and coming back from a badly broken leg - which could pretty much finish careers then. In addition to that lot, Geoff Palmer had been at the club for nearly 10 years, and so was running the risk of getting stale. The remainder were simply not good enough for where Wolves wanted to be. Whilst that sounds very harsh, just look at their careers post-Wolves. Paul Bradshaw's career was pretty much wrecked by his back injury, Andy Gray had success in the top division, but all of the others settled down as Second Division (or worse) squad players, with the exception of Peter Daniel, who fell down the divisions as quickly as Wolves did, finally ending up at Burnley and playing in a certain Sherpa Van Trophy final...

You can't accuse Barnwell of not trying, though. For various reasons, players he lined up for the club such as Michel Platini and Peter Reid did not arrive. The sale of Steve Daley for cash up front, followed by signing Andy Gray on instalments was an example of his thinking. The signing of Emlyn Hughes put a marker down on his ambitions, as he figured that his experience, whilst it was only ever going to be available to us for a couple of seasons, would stabilise the side in the short term, to enable a decent longer-term future. I have come to a simple conclusion though. In hindsight as far as the team is concerned, the signing of Andy Gray was a mistake. Yes, his goals helped us to a good league position in 1979-80. Yes, he scored the winning goal in the League Cup final. When you look at the players that needed replacing soon, though, it would probably have been better for us if we'd have bought six £250,000 players instead of blowing £1.5 million on one slightly injury-prone forward. In those days, £250,000 bought you a very good player.

Molineux

Let's not beat around the bush here. In the 1970s, Molineux was a disgrace. Pretty much nothing had changed in the stadium since the days of Stan Cullis, and the whole place was slowly falling apart. Since the 1950s, Wolves showed off big plans to upgrade Molineux, and it seems that these plans were used as an excuse to not upgrade the facilities that were in place. The North and South Banks were scruffy, with bits of patched roofing all over the place, the Waterloo Road stand was looking slowly more and more dilapidated, and the Molineux Street stand was a hazard under the Safety of Sports Grounds Act 1975. It needed replacing before it was closed down, and so the New Stand (as it was known then) was born; and with it a larger plan to replace the entire stadium by the end of 1984.

The New Stand

It's commonly believed that the interest payments on the New Stand is what pushed Wolves into receivership in 1982. Is that fair? Well, looking at the historical data, it doesn't seem to be the whole story. The stand opened in 1979, so let's look at the annual average interest rates for the "big four" banks for around that time.

1975 - 11%

1976 - 11.11%

1977 - 8.88%

1978 - 9.31%

1979 - 13.69%

1980 - 16.31%

1981 - 13.27%

1982 - 11.9%

1983 – 9.82%

Whilst those interest rates seem horrendous at the time of writing, they're actually what would be expected up to around 1992, when rates dropped to a level more familiar with us now. It can also be noted that by 1981, before receivership, the rates had already peaked and were on their way back down again to rates similar to those when the go-ahead for the stand was given! In short, Wolves should have budgeted for costs around the 1981/82 figures as being perfectly within the range of expected expenditure. The stand was reported as costing somewhere between £2.5 and £10 million, with the larger figure likely to be for the entire stadium rebuild. Either way, that's an absolutely huge amount of money for the time. Adjusting for inflation, that makes the larger figure £38 million in 2010 money. Or, to put it another way, about what Steve Morgan told us then was the figure for upgrading three stands at Molineux, to the standards of 2010, with loads of extra facilities within that would not have been planned for in the 1970s. It should also be borne in mind that inflation within the construction industry is much higher than average, so it would be fair to suggest that the new stadium was costed at vastly more than Steve Morgan's vision of Molineux.

Granted, Wolves needed to buy up most of the houses on Molineux Street to get the land upon which to build (given that the New Stand was built on the opposite side of Molineux Street to the old stand), but housing was relatively cheap back then. If the cost was nearer the £10 million end of the quoted figures, then what on earth cost so much? And given the vast sum of money, how on earth did Wolves think that they could revamp the entire stadium? However, if it was as low as £2.5 million, then two more things don't make sense.

Firstly, the Andy Gray transfer. If you're a prudent chairman, then probably you'd have kept a fair amount of the Steve Daley money back in order to either pay off or service the loan instead of allowing your manager to blow the lot on a single player. Sure, you'd have let Barnwell spend some of it, but no more than (say) £750,000 rather than £1.5 million! That would have instantly cleared most of the debt. If the cost of the stand is nearer the £10million, then it doesn't make a vast amount of difference either way, so you might as well let Barnwell blow the lot.

Secondly, if you imagine that worst case scenario, Wolves borrowed the entire cost of the stand. So, let’s do the maths. The interest for a year at those rates on £2 million in 1981 rates is roughly £250,000, which is pretty much exactly the same cost as in 1979 when the stand was completed, and only about £60,000 annual difference from any 1978 projections using 1978 figures. So how on earth did the club collapse with debts supposedly of over £2 million, especially if they were sensible enough to use some capital for the initial outlay? And the interest rates in 1977-78 were changing rapidly, sometimes literally weekly. Anyone with any sense would realise that the short-term lower rates of the time were unlikely to stay.

The Receivership itself

Why did Wolves go into receivership in 1982 at all? People from the time have testified that Wolves were actually solvent, and could service their debts. It has been alleged that it was simply a ruse by the then-chairman to ditch some of the club's debts, and thereby make a profit on the deal. Who was that chairman? “Deadly” Doug Ellis, more famous as the long-time chairman of Aston Villa; and that connection has led to speculation that it was done deliberately in order to push Wolves out of the picture to the benefit of our good friends in north Birmingham. As tempting as that particular conspiracy theory sounds, it should also be remembered that his deputy chairman was Malcolm Finlayson, the former Wolves goalkeeper of the great side of the late 1950s and a successful businessman in his own right; and not the kind of figure that you’d normally consider as wishing closure on the club.

If Wolves had not gone into receivership, then the Bhattis would never have been able to buy the club. Simple. Something else to bear in mind however, is that it has been claimed that a certain Sir Jack Hayward was actually the largest bidder for the club before the Bhattis' "last three minutes" bid. It is worth considering quite what Sir Jack might have done for the club in terms of investment, when he was nearly ten years younger than when he actually took over, at a time where £1 million bought you a top-class player.

Wolves (and Ian Greaves, who some believed at the time was the best Wolves manager since Stan Cullis) despite the relegation and receivership may well have been able to replace the aged players and built a side around Andy Gray. Wolves would certainly have had a good chance of then continuing to compete in the old First Division and would likely have been quite happily at the top table when the big money arrived in the game in 1992.

The long-term effect

It’s so easy for those outside Wolverhampton to forget the stature of the club back then. Between 1972 and 1982 we were three time FA cup semi-finalists and twice League Cup winners, UEFA Cup finalists, and UEFA Cup qualifiers four times in eight years. To put that in some perspective, other than the “Sky Six”, in the last ten years no club has managed more than two European qualifications; or won the League Cup twice, or been in the FA Cup semi-finals more than twice. Following the receivership, as we all know we fell through the divisions, going from top to bottom in successive years – something no other club, not even Portsmouth, Blackburn, Bolton, Sunderland or any of the 21st century problem clubs have “achieved”. We went from UEFA competition in 1980-81 to pretty much bottom of Division Four in 1986. And we did all that at exactly the wrong time. As mentioned above, it’s quite likely that without the 1982 problems, or if Sir Jack had won after the receivership, that Wolves would have been sitting pretty in the top division when the Premier League came along. Then, who knows? It’s certain that it’s taken the club until now, 2020, for the mistakes of forty years ago to be reverted.

Conclusion

The more I think about this, the further back you can see the problems of 1982 coming. Wolves were not renowned as being big payers of players, and there was barely any money spent on Molineux. Transfer fees roughly matched in and out of the club, so we weren't spending our money there. So where did it go? The true answer to that question is probably lost in the mists of time. So where does the blame lie? Personally, firmly at the feet of John Ireland, with a helping hand from Harry Marshall and Doug Ellis. Yes, the man that Wolves fans love to hate for the ridiculous sacking of Stan Cullis is yet again cast as the bad guy.

If Ireland had kept Cullis, then a more successful 1960s was likely. This would have led to more money in the club, some of which should have been spent on stadium maintenance and improvements. If he had done that, then Harry Marshall would not have inherited the desperate need to replace the Molineux Street stand. Marshall should have asked more questions about the amount of money for the New Stand and how we could ever have afforded it, which would then have allowed for the team restructuring that Barnwell desperately needed in order to keep the money in. And finally, Ellis should have kept the club safe instead of playing Russian Roulette with its future by gambling on being able to buy the club back cheaply, a fateful decision that has taken Wolves 40 years to recover from.